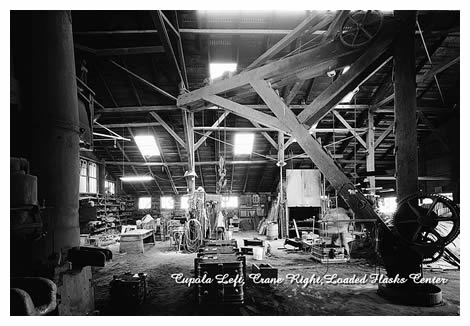

KNIGHT FOUNDRY … HISTORIC OVERVIEW

Historic Knight Foundry – Water Powered Foundry & Machine Shop. A look back.

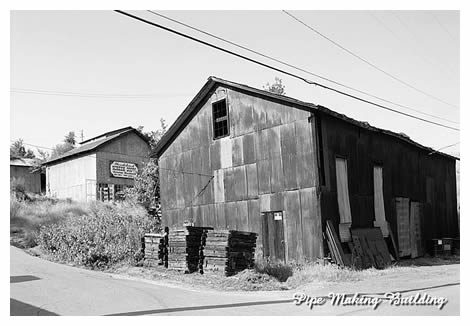

The Knight Foundry is one of the best preserved 19th-century industrial-age workplaces in the United States. It was in continuous operation in Sutter Creek, California for 123 years, from its founding in 1873 until 1996, at which time it was designated one of the country’s eleven most endangered historic sites by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Today few other sites are in a comparable state of preservation. Nearly a quarter century since its closing, Knight Foundry remains virtually intact.

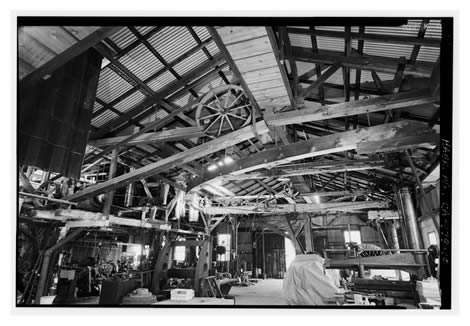

Knight Foundry never significantly modernized; the original machinery is still powered by patented Knight Water Motors via a system of line shafts and belt drives. In addition to a full complement of tools and machinery, no other site preserves an unbroken line of nearly extinct foundry skills down to the present. These skills associated with the foundry craft are another unique element of the site’s historic fabric. And Knight Foundry isn’t just an old foundry: Samuel N. Knight (1838-1913) and the other skilled artisans who worked there were a major, albeit unsung, source of technological invention, innovation and engineering for early California industry. Knight Foundry truly is an endangered national treasure.

EARLY HISTORY

Knight Foundry has come down to us in such an astonishing state of preservation because, for a variety of reasons, the successive owners did not want to, need to, or could not afford to, modernize it. At the outset the iron works, as set up by Campbell and Hall in 1872 to build impulse water wheels and hard rock gold mining equipment, was a well-integrated, state of the art operation that could readily accommodate expansion of production.

Samuel Knight, born in 1838 in Maine to English parents, was first apprenticed as a ship’s carpenter. Leaving that trade, he worked in a machine shop in Florida, thus acquiring metal working skills. Around the time of the Civil War Knight came to California where he worked in the gold mining district as a millwright, eventually connecting with Campbell and Hall and their foundry in Sutter Creek. The Campbell and Hall foundry quickly came under the control of Knight, who renamed the foundry Knight & Co. in 1873 (this date has commonly been used as the founding date).

WATER POWER INFRASTRUCTURE

Knight was well aware of the development of water power applications for running mills and factories in the eastern United States, which had led directly to the development of the reaction water wheel. Water supplies in the east were characterized by plentiful year-round flow in rivers with a gradual drop.

Thus, reaction water wheels relied on high volume and low pressure to generate power. In the west, opposite conditions prevailed: highly seasonal supply and steep gradients, in the Sierra Nevada particularly.

Thus, reaction water wheels relied on high volume and low pressure to generate power. In the west, opposite conditions prevailed: highly seasonal supply and steep gradients, in the Sierra Nevada particularly.

The development in the mid 1850’s of hydraulic mining addressed these different conditions by collecting water from multiple watersheds using ditches and flumes and then employing very high heads of pressure developed within cast iron penstocks dropping hundreds of feet vertically to supply the monitors. It was this readymade high pressure water infrastructure which suggested the development of a water wheel system very unlike developments in the east: the impulse water wheel.

As it happens, in 1873 the Amador Canal and Mining Company completed a canal system which brought water supplies to Jackson, Sutter Creek, Amador City and Ione. The Amador Canal water originated in the North Fork of the Mokelumne River where it was first diverted for hydraulic mining purposes in 1855. Water was captured from the Mokelumne at the Electra Diversion Dam, passed through several miles of the Electra tunnel to Tabeaud Reservoir, where it was then pumped into the Canal’s headworks. The Canal passed over the South, Middle and Main Forks of Jackson Creek to reach Tanner Reservoir above Sutter Creek.

It was the newly available high pressure water which inspired millwright Samuel Knight to first develop the impulse water wheels which eventually became the prevalent prime mover of Gold Country industrial equipment. Water from the Amador Canal was directed to an inverted siphon that acted as a penstock for the foundry and where it crossed the creek a pressure reduction valve released water to the foundry at a pressure of about 120 psi.

The first impulse wheels were wooden ‘hurdy-gurdy’ wheels, where the jet of water was directed against a wheel shaped like a circular saw blade. Samuel Knight made a series of improvements to this wheel adding metal buckets and finally creating a one-piece cast iron wheel which he patented in 1875. His role as innovator is not clearly delineated, but research indicates that he had a defining role in this development. His wheel had a rectangular bucket that exhausted water toward the center of the wheel. At that time a number of manufacturers, including Donnelly Foundry in Sutter Creek, were also making impulse water wheels. Knight’s was distinguished as the only one-piece cast wheel; others bolted or riveted separate buckets to the wheel. The production of Knight’s bucket demanded the highest level of pattern making and molding skill due to the complexity of the cores involved. Under Knight’s leadership, and with the Knight Water Wheel as a signature product, the company was at the forefront of industrial technology development until after the turn of the century. For a period of time, Knight & Co. was the largest foundry and machine shop outside of San Francisco, at its peak employing 44 workers.

In 1878, water wheel designer Lester Pelton observed a Knight wheel in operation which had slipped off the key on its shaft with the result that the jet of water struck the bucket on one edge and was thrown off the other side. The speed of the wheel was increased as a result of the water not striking the wheel center and interfering with the jet. Based on this observation, he developed and patented the twin bucket Pelton wheel design which he began manufacturing in Nevada City at the Nevada Foundry (the building preserved today as the Miners Foundry).

In 1883, a watershed event took place in nearby Grass Valley. The Idaho Mining Company conducted a trial of competing water wheels to determine their relative efficiency. The Pelton wheel won at 90.2%, compared with 76.5% for Knight wheel, 69.6% for the Fredenburr wheel and 60.5% for the Taylor wheel. The Grass Valley trials were to make Pelton’s fortune. Around the turn of the century W. A. Doble applied a somewhat more scientific approach to impulse water wheel design and significantly improved efficiency by introducing an ellipsoidal bucket and cutting back the lip of the bucket to create a better transition into the water jet. Doble eventually took over the Pelton company to manufacture wheels of his design but did not change the name of the company or the product, perhaps because of the value of the established name recognition. Pelton wheels are still in widespread use today, with improvements over time having increased power efficiencies up to 96%. The impulse water wheel thus continues to have an important role in power generation all over the world.

Knight continued to develop and produce water wheel driven systems and other equipment through the early 20th Century. Early and unique developments included a double water wheel with wheels set in opposite directions on the same shaft for hoist works, so the hoist operator could control his reels with one lever, up and down. This required sophisticated valving devices. Later Knight developed, patented and manufactured complex water wheel governor systems to keep rotational speed within one percent for application in some of the earliest hydroelectric plants in the West. To this day, Knight Foundry itself is almost entirely powered by Knight Wheels and was the last remaining industry served by the local water-power system via the Amador Canal.

A NEW CENTURY

In the early years of the new century, machine tools were being equipped with separate electric motors, but Knight & Co. retained its efficient water-driven line shaft system. After Knight’s death in 1913, the company was owned by a group of four employees, to two of whom Knight had left shares. Dan Ramazotti became principal owner in 1920. After the low ebb of mining business during World War I, Knight & Co. had a period of prosperity as the mines expanded their operations, providing machinery for the Kennedy and Argonaut mines locally. Master molder Wendell Boitano remembers, “The last hoist they made was for the Argonaut mine. It was an underground hoist. They put it together in the foundry here, in the machine shop, and tried it out first, to see if it’d work, you know, then took it all apart again. They put it all together down there underground again. And it’s still down there.” The Argonaut went down nearly a mile. Since the pumps have long been silent, that hoist is under hundreds of feet of water today.

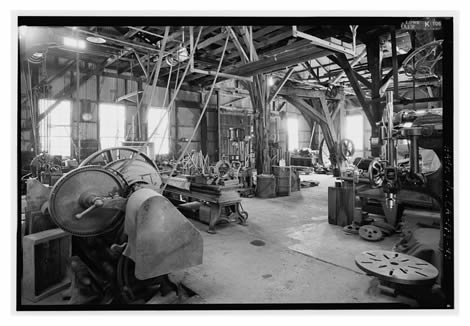

During this period machine tools had evolved as harder, heat resistant cutting bits allowed higher speed operation, but again Knight did not replace its original machinery. World War II brought another slump in business; the shop was not refitted with modem equipment as it was not a strategic industry.

As Knight & Co. was set up to build large scale custom machinery, it never had the molding floor or furnace capacity to produce anything by the hundreds. Thus, as the 20th Century progressed and business fell off, Knight & Co. was increasingly restricted to the narrow niche of custom production of typically larger size castings, serving its old industrial customers with replacement parts. In 1949, Ramazotti retired and divided his shares among the foundry employees. They worked the foundry but probably never had enough money to make serious capital improvements. In 1956, Herman Nelson bought the foundry and ran it until 1970, when he suddenly passed away.

THE MODERN ERA

In 1970 aerospace engineer Carl Borgh, who previously had castings made at the foundry, upon learning of Nelson’s death made the remarkable decision to acquire and operate the old foundry, leaving the high-tech world for what he regarded as a historic treasure. It is at this point that a conscious effort to preserve the foundry as a historic workplace became a significant factor.

Carl had a keen appreciation for the site itself, but also a respect, borne of his own technical background, for the skill, experience and sophistication of Knight’s workers. Interviewed in 1995, Carl said, “I was fortunate when I bought the foundry to have a group of highly skilled craftsmen who agreed to stay on and help me run the foundry. Without their expert help, I could never have done it. I was their apprentice; l was the novice; they taught me the things I needed to know.”

While there had been a number of suggestions over the years that the iron works be opened to the public as some sort of museum, Carl felt that just running the foundry as a business was about all he could handle. By 1991, with the American foundry business in a deep slump, Carl was ready to close down operations. He was soon approached by a group of local residents led by Ed Arata (whose grandfather Elbridge Post had been a machinist at Knight & Co.) with a proposal to keep the place in operation and begin development of the site as a living history museum.

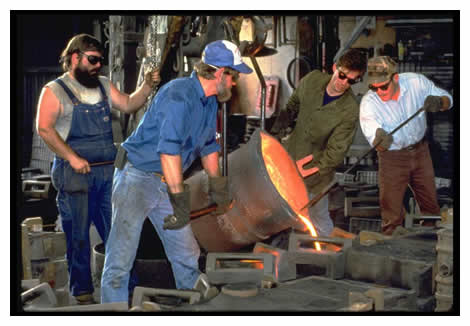

In 1992, Ed and his colleague Robin Peters formed Historic Knight & Co. Ltd. to continue production and raise money to acquire the site. Their innovative Industrial Living History Workshops – three day sessions during which participants could make patterns, learn green sand molding and participate in a pour of molten iron – attracted people from all over the country and contributed greatly to a growing realization that Knight Foundry was a unique national treasure. Along with being designated one of the National Trust’s 1996 Eleven Most Endangered Historic Sites, Knight Foundry was also placed on the National Register of Historic Places, was designated a State of California Historic Landmark, and was named a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Historic Knight & Co. kept the foundry alive and passed on foundry skills to a new generation of volunteer workers. Volunteers like high tech engineer Sam Thompson also did a great deal of work in restoring the machine tools to working order. After a valiant four years of effort, Historic Knight & Co., about to go into the red, discontinued its efforts in 1996. Carl Borgh, still the owner, made a final pour in July of 1996 and then padlocked the doors.

Soon thereafter, a number of participants in that effort regrouped, carefully studied the problems encountered by Historic Knight & Co., and launched a renewed effort to save Knight Foundry. The new group, who had initially met at the foundry, were united by a shared and generalized concern for the ongoing loss of historic industrial skills. Organized in 1995 as the Industrial Living History Consortium, the distinctly multi-disciplinary group conducted a series of symposia bringing together experts from a variety of fields to confront the complex problem of deriving a methodology for industrial skills preservation. To bring their work into a broader organizational context, they founded a chapter of the national Society for Industrial Archeology, which they inaugurated, appropriately, as the Samuel Knight Chapter.

In 1997, the Chapter Board approached Carl Borgh with a proposal to revive the Knight Foundry preservation effort. After giving the group all the responsible discouragement he could, Carl gave a tentative go-ahead and the Chapter put out a call to former participants. The response was gratifying; sixty-eight people gathered in Sutter Creek in January, 1998 and spent the day discussing the situation. The Save Knight Foundry Task Force was formed under the aegis of the Chapter; with the help and encouragement of the National Trust for Historic Preservation a formal Strategic Plan was drafted. The City of Sutter Creek agreed to administer a Samuel Knight Preservation Fund to accept tax deductible contributions and by the end of 1998, solid community support for the project and a substantial amount of money had been gathered. Carl agreed to not sell off or dismantle the foundry in return for a nominal monthly lease, with this amount to be applied to the purchase price. Tragically, Carl passed away in October of 1998.

In the mid-1990s, while still operating as a working foundry and machine shop, multi-day industrial living history workshops were developed together with tours and educational programs for adults and children. The level of interest those programs generated was remarkable, bringing visitors from all over the world to witness, in real time, operation of the last water-powered foundry and machine shop in the United States.

In 2000 the property was purchased from the Borgh family by Richard and Melissa Lyman in an attempt to hold the complex, in its intact state, until a suitable entity could muster the resources to acquire and preserve it in perpetuity. The Knight Foundry Corporation, a non-profit entity, was organized in 2000 for just that purpose, assembling a board of directors recruited from the historic preservation, non-profit administrative, museum and industrial manufacturing worlds. The Knight Foundry Corporation focused extensive effort on planning, acquisition and appraisals, and from 2000 to 2004 operated heritage tours and educational events that had been developed to a high degree of refinement. A variety of educational programs were pilot tested, and several grants were obtained for planning and preservation. Working in conjunction with the City of Sutter Creek, a serious effort to purchase the site, partially grant-funded, grew and then failed. In 2015 the Knight Foundry Corporation, finding itself without the energy or resources necessary to proceed forward, terminated its operations and the entity dissolved.

TODAY

Many years ago the City of Sutter Creek recognized Knight Foundry for its historic significance in the Historic Element of its General Plan. Preservation of the site was a long-time goal of the City but despite the efforts of many, acquisition remained elusive and the facility seemed destined for demise. In a late 2016 breakthrough, however, the Lyman family agreed to a generous two-step plan calling for donation of the land and buildings followed by purchase of the historic contents. Recognizing this as a “last, best” opportunity to preserve the complex in its original condition, the City Council agreed and the purchase was completed in April 2017 through the unprecedented generosity of hundreds of individuals, families, and organizations who love Knight Foundry and wanted to see it preserved.

The significance of acquiring and preserving this 19th-century wonder began to show as soon as the doors were reopened to visitors for the first time in nearly two decades, on March 4, 2017. Nearly 1,200 people visited Knight Foundry on that day! Since then, the Foundry’s operating entity, Knight Foundry Alliance, has begun offering public guided tours on the second Saturday of every month, as well as a growing calendar of special events and volunteer opportunities. Hundreds of volunteers from all over northern California have been working on cleanup and restoration. The Foundry’s operating entity, Knight Foundry Alliance, is actively raising funds in order to meet the next big goals: to implement urgent security and stabilization repairs, and to preserve and protect the archives of the Foundry’s long history.

Plans are for the Foundry to serve as a living history museum and an educational resource that provides a unique window into Amador County’s and California’s history and heritage. You can help us continue the work of restoring and preserving Knight Foundry and its history by becoming a volunteer, or donating your time or money. All donations are tax deductible to the fullest extent of the law.

The Knight Foundry complex is the crown jewel in a world-class industrial heritage corridor that tells the story of how local industry created, and then contributed to, the viability of Sutter Creek and other communities of the Mother Lode in Amador County, California.